Much has been written about the female convicts sent to our shores. Nearly 25,000 were sent and around 10,000 of them spent time in one of the numerous female factories which existed in New South Wales and Tasmania.

In all, there were 12 operational female factories. In the colony of New South Wales there were two at Parramatta (with the new replacing the old), one at Newcastle, Bathurst and Port Macquarie, and two at Moreton Bay. In the colony of Van Diemen’s Land there were five – Hobart Town, Cascades, Launceston, Ross and George Town.

At first, the numbers of female convicts transported to the colony were not problematic. They became servants, housekeepers and wives. As the numbers increased, the authorities had a problem because of the sheer imbalance of numbers with one female to every four males. If morality was to be encouraged, there was a need to separate the sexes so that there would be fewer sex crimes and less prostitution. Those who re-offended, as well as women who were given colonial sentences, had to be punished, so the female factories played a very important role.

It was not until 1st January 1829 that the Colonial Secretary published the Rules and Regulations for the Management of Houses of Correction for Females. The roles of the Superintendent, the Matron, and the other officials were more clearly defined.

Governor Hunter, in 1796, had asked that no more female convicts be sent as there was no employment for them.

Nothing can be more distressing to the serious reflecting mind than to see the vices and miseries of these abandoned females. When I am called upon in the hour of sickness and want, to visit them in the General Hospital, or in the wretched hovels where they lodge, my mind is oppressed beyond measure at the sight of their sufferings. [Quote by the Reverend Samuel Marsden.]

The wretched hovels would have referred to the nine huts at Parramatta which accommodated the unmarried girls. The agricultural settlement set up by the government at Toongabbie placed a number of females as hut-keepers to cook and clean the huts, each of which housed eighteen men. But there was a problem with what to do with the women and how to house them when they arrived, especially as the numbers of new arrivals continued to increase.

Governor King saw a solution to the problem when the new gaol was being built in 1800 at Parramatta. It was completed in 1804 just in time to accept the women who came on board the Experiment. However, space was limited, and, as more arrived, it was impossible to house them all. The women were employed in spinning and weaving wool in this Female Factory. Those who were well behaved were available to be selected by settlers as housekeepers or servants or ‘wives’. Those who misbehaved stayed in the Factory or were sent to the coal mines in Newcastle.

A fire in December 1807 caused damage to the Factory. By then there was chaos in the colony with the overthrow of Governor Bligh. When Governor Macquarie arrived he had to address the conditions in which the female convicts were living. The British Government envisaged the women being assigned in apprenticeships, living with a family on a permanent basis. Marriage was the only way such an apprenticeship could be terminated.

While in England, in 1808, Reverend Marsden drew attention to the conditions endured by the convict women, and was assured that barracks would be built for them. After the Napoleonic Wars (from 1815 onwards) the numbers of both male and female convicts increased dramatically and Governor Macquarie’s pleas for the new barracks seemingly fell on deaf ears in Britain until 1817.

In 1818, Marsden submitted a plan which he felt would be apt, and Governor Macquarie instructed Francis Greenway to prepare a plan for a Factory and Barracks at Parramatta to house 300 women in an area of 4 acres to be enclosed with a wall. The building was to be three storeys high. The stone to be used in its construction was to be obtained from a local quarry. Work commenced in July 1818 and was completed in January 1821.

The Governor visited the site not long after building had commenced. He wrote –

After breakfast, went to the Place selected for building the Factory and Barracks on the Left Bank of the Parramatta River, where I met Mr Greenway, the Government Architect, and the Contractors, Messrs Watkins and Payten, and at 12 o’clock laid the Foundation Stone of this new Building in the usual Form, giving the workmen Four gallons of Spirits to drink success to the Building.

The new Factory had numerous functions-

- housing newly arrived female convicts

- a place of secondary punishment

- a refuge for the elderly and infirm

- a marriage bureau {Many women preferred marriage to placement in the institution. Although many of these marriages seem to have been successful, it was not unusual for some to separate from their newly acquired husbands.}

- a place for redistributing females on assignment

- manufacturing cloth {Records, in 1822, show that more than 6,000 yards of cloth was manufactured in the factory. In later years, sewing and laundry work were done.}

- a hospital for accidents, illness and birthing

Under Governor Macquarie, the women were grouped into two classes. The General Class comprised of the aged, the married and the young. After six months of good behaviour, as an incentive, the women in this class could graduate to Merit Class where they could earn their own money. After 12 months in Merit Class they could be assigned or allowed to marry. There was also a Crime Class for repeat offenders.

In 1826, Governor Darling ordered an inquiry into the Female Factory and a three class system resulted. First Class was for new-comers and the destitute. Second Class was for pregnant and nursing mothers and also a transition stage between First and Third Class, the latter being for repeat offenders. Here the hair was close cropped and hard labour was performed.

There was a revolt at the Factory in October 1827. The Sydney Gazette reported that the cause was the substitution of salt for one ounce of sugar which had been previously allowed for the women of the third class for the morning meal. The women took possession of tools and smashed one of the gates and entered the town. They raided butchers’ and bakers’ shops. In the turmoil, 19 women escaped.

In 1839 a new block of 72 cells (in 3 tiers) was built to house women with colonial convictions. Prior to this secondary offenders had been transported to Moreton Bay, but with closure of that settlement, cells were required for their confinement. Magistrates were able to order imprisonment in solitary or dark cells on bread and water for not more than 21 days at a time. Dark cells were 8ft long, 5ft wide and 9ft high. There were the 36 cells on the lower tier. Criticism of the dark cells in an 1840 report led to them being altered in such a way that light was admitted. A result of the report was that solitary confinement was abolished and assignment from the Factory ceased.

July 1842 saw the maximum number of women in the Factory – 1203. Governor Gipps was urged by representatives of the Factory to revive assignments. He wrote in October –

Their manner of addressing me was still respectful, but there was an air of determination in it which was altogether novel; and the peculiar hardship of their conditions was, I perceived, perfectly understood by them. They represented that they had been sentenced to be Transported, but not to be imprisoned after Transportation, and contrasted (and I must say with great force and truth) their condition with that of the Women in the Penitentiary at Millbank.

Recommendations were for changes in the diet and the reduction of the numbers of inmates. A modified system of assignment was also to be introduced. However, there was still discontent and another revolt occurred.

On the evening of February 1, 1843, two women were discovered by the sub-matron to have scorched themselves for the purpose of escaping or attempting to escape. They were ordered into confinement, but called for the assistance of the women who had been locked up for the night. The women in the adjoining ward forced the doors and rushed to the assistance of the two prisoners mentioned; but they had been clapped into cells and locked up. A regular riot ensued, which was not quelled until the police and military were called in. Eighty rioters were secured before daybreak and lodged in cells in the Gaol or the Factory. Heavy rain fell soon after the commencement of the fray, and this probably prevented the women from setting fire to the building.

In 1846, the Governor referred to the women in the Factory as the very refuse of the convict system. By the end of the following year the decision was made to close the Factory. The remaining women were discharged or given tickets of leave. Only invalids and lunatics remained.

Emu Plains

Although there was no factory at Emu Plains, a number of female convicts were sent to the agricultural establishment there in 1822. This did not prove to be morally successful and was discontinued.

Newcastle

A gaol was built in 1818 to take secondary offenders. By 1823, settlement in the region had demanded that the convicts be removed to a more remote location. The gaol then acted as a repository for both male and female convicts who were being assigned to settlers in the Hunter Valley. In 1830 there was discussion about using the gaol as a place for ‘incorrigible women’ but it was not cost effective. In 1831 a riot at the Parramatta Female Factory resulted in 37 women being sent to Newcastle, and from 1831 to 1846 it was known as the Newcastle Gaol and Female Factory.

Bathurst

Expansion to the west after the crossing of the mountains meant that there was a need for female servants in the newly settled areas. After problems with transporting women by dray from Parramatta it was not until 1832 that the military barracks at Bathurst were converted to a Female Factory to house females awaiting assignment or confined as punishment.

Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie was established in 1821 as a place for secondary punishment and a number of women were sent there. A crude building housed 50 women at a time but it was inadequate and most were assigned as servants in the town. It was soon evident that there were not enough employment opportunities and the girls objected to being confined when they had not committed secondary crimes.

In 1830, Port Macquarie ceased to be a penal settlement and it was opened to free settlement. The Factory was to be used from then as a place for Third Class females only. With the end of transportation in 1842, the Factory was closed and the remaining women were sent to Parramatta.

The Women at Moreton Bay.

According to the 1828 census, Catherine Buckley who arrived on the Providence was sentenced to serve time at Moreton Bay for 3 years. Also serving a 3 year sentence was Marie Wade who arrived on the John Bull. Elizabeth Robertson who sailed on the Friendship had been given a 7 year sentence. Elizabeth Pearse of the Mary is listed as being a volunteer. She appears to have accompanied James Pearson (no details of occupation or sentence) who also arrived on the Mary.

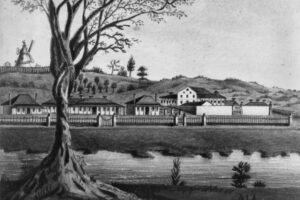

Between 1829 and 1837 it is estimated that 135 convict women were at Moreton Bay. Originally they were housed in a building on the present site of the G.P.O. and it is reported that one of their tasks was to make straw hats for the men.

Commandant Patrick Logan established an agricultural settlement at Eagle Farm in September 1829. It was eight miles from the main convict settlement. The site was cleared by 150 male convicts, and by January 1832 about 680 acres were under cultivation. Maize was the main crop but potatoes were also grown. A number of livestock included pigs and cattle. Female convicts were recorded as being at Eagle Farm from as early as 1830.

Despite the concerns about the increase in the incidence of malaria because of the swamp land, the farm continued to operate. Clearing work continued, but by 1836 only 46 acres were being utilized for crops.

Despite the concerns about the increase in the incidence of malaria because of the swamp land, the farm continued to operate. Clearing work continued, but by 1836 only 46 acres were being utilized for crops.

By 1836 there were forty female convicts working at Eagle Farm. There had been a need to separate the women not only from the male convicts but also from the military. Although the men were ordered not to cross the bridge at Breakfast Creek, the rule was not always obeyed, so it became necessary to provide better and more secure accommodation for the women.

When the new Women’s Prison and Factory was completed in 1837, all of the female convicts at the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement were transferred there.

The buildings included a Supervisor’s cottage with a detached slab kitchen; a two-roomed hut occupied by male convicts; a two-roomed hut with a detached slab kitchen for the Matron; a number of four-roomed buildings for the women; a store, a hospital, a school, and a workhouse (all one-roomed); a two roomed building for the cook house and needle room; and a block of six cells. A double fence surrounded the establishment. The outer fence was 17 feet high.

It was late in 1838 that the decision was made to close the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement, and by July 1839 the women had been removed from Eagle Farm and it was used as a government cattle station. In 1842, the land was surveyed and auctioned. The buildings were later demolished.

The above information about the Eagle Farm Women’s Prison and Factory can be found on the Queensland Government Department of Environment and Resource Management web page. The original site of the female factory has long been covered with land fill as it became a part of the old Brisbane Airport in 1942. The location of the site is in the vicinity of Schneider Rd and Amy Johnson Place.

Van Diemen’s Land

It was not until 1817 with the greater influx of transported felons that suggestions were made to establish a female factory in Hobart. Prior to that time, the numbers of females were small enough for the women to be absorbed into the colony. However, Governor Macquarie had decided to build the Parramatta factory and did not intend sending more women to Van Diemen’s Land. Those women requiring extra punishment were sent to Sydney, Newcastle or Macquarie Harbour up to 1825, but they were not large numbers.

Hobart Town

The gaol in Hobart Town was completed in 1818 and a room was set aside for female prisoners. Despite requests for a female factory, permission was not granted until 1821 after the inquiry into the treatment of convicts by Bigge in 1819. The factory was built beside the gaol but there was often not enough work for them to do or indeed enough equipment available for them to use.

An inquiry was held in 1826 as over-crowding had become a problem and women had been escaping. Plans had been made to build another factory at Cascades, near Mt Wellington, on the site of the old rum distillery. When it was completed in late 1828, the women were moved there from Hobart Town.

You may be interested in deciphering the following letter which was published by the editor of the Hobart Town Courier on Saturday, 7 June 1828, on page 3, column 2. It was intended for Mary Anne who was in the Hobart Town Female Factory:-

The following letter was delivered last night at our Office, in Liverpool Street, we suppose, in mistake for the Female Factory. As there exists some difficulty in transmitting letters of business to the inmates of that establishment, we here publish it for the benefit of all concerned.

Jericho, May 28, 1828.

My dear Mary Anne,

I sees the first safe and, since I ave bin eer to ryte to you, which I does by Kunstaple ‑‑‑‑‑‑ who is going to camp to‑morrow morning with poor Jim who as got into trooble. I ave giv him a doller, with wich he has promessed to by you a drop of summut, wich I ope will be sum cumfurt to you in yoor present doll cityashun. I was very soryy my last tryall to git you ought did not succeed. Mr Lacklane found it all ought ass you no. For all thatt I ope you will not be fals to me, for I have a plann in you by wich I think I shall be to git back to camp, and to git a frind to take you oaf. My merster kips a number of milking cows and a large diary awl very reglar, and I expex he will send me to camp with the nixt lode of butter. He as also a number of marine ship and takes a grate deal of pens with the owl, wich he intends to pack up carefooly and send a way by the Call Easter, now loding in the arbour. You need nivirr be jellies of me for I think of nothing but my dear Miss Mary Anne and her lovly fase day nor nytr, from your loving and halfexshonat lovyer.

Poss Kripp. Do not forget to send a loin by the Kunstaple who will be on iss gurney back in a boot a week. I ave written some loins of pottery on you, wich I will send you nixt time. Send me a Kurrier with the camp noose.

Yours till death.

The Cascades

The Female Factory at the Cascades was opened in December 1828 and women from the Hobart Town factory were relocated there. The new regulations defining the roles of those employed at the various female factories were put into place. Despite the strictness of the guidelines to be adopted, there were problems as there were at the other factories – problems of overcrowding, corruption, under-staffing, and inadequate rations. As more women arrived, the building was extended. At first the women were housed until assigned, but as more were placed there in the Crime Class and Probation Class, more problems with controlling the ladies resulted and rioting occurred.

Between 1841 and 1843, new regulations meant that new arrivals had to undergo a six month probation period before being sent into ‘service’. Some of the women spent this probation time on board the hulk Anson on the Derwent River.

The Cascades was under British control up until 1856 when it ceased to be used as a female factory and instead was used as a gaol until 1877.

George Town

The Female Factory here began operating around 1822, much the same time as that at Hobart Town. George Town (or Port Dalrymple) on the Tamar River had been settled since 1804. A shed in the lumber yard was used by the women to make leather shoes and to make cloth as a form of hard labour until 1825. The women did not live there. They found lodgings wherever they could.

When Reverend Youl moved from George Town to Launceston, his residence was converted into use as a female factory. By 1830 it was in a dilapidated state and there were problems with overcrowding and security and not enough work or equipment. It was closed in 1834 when a new factory was available in Launceston where the greater part of the population in that area had settled.

Launceston

The Female Factory here commenced construction in 1831 but was not completed until 1834. It was built to house 68 women and 11 children – but was soon over-crowded when transportation of convicts to NSW ceased and convicts were sent directly to Tasmania. Discipline became a real problem and rioting occurred.

When a hiring depot was established between 1844 and 1848, separate from the factory, it meant that the overcrowding eased and the factory became a place for punishment as well as continuing as a nursery. Infant deaths here, as at the Cascades, were rather high.

When Ross opened in 1848, the infants and their mothers and the pregnant women were moved there from Launceston.

Ross

As settlement spread between Hobart and Launceston, it was often the problematic convicts who were assigned to the more remote areas. Naturally they continued to be a problem and there was a need for a place of punishment as well as a place to hold women until they were assigned to the settlers. Ross was chosen as the site for the last female factory to be built. It would also act as a secure place when transferring prisoners between the two major towns. Being built at a later date, it was more commodious and in a healthier climate. Fewer babies died here, but the factory was not without its problems. The behaviour of many of the women left much to be desired. The factory closed in 1855.